Exploiting ApprovalTests for clearer tests

What's this for?

Ever written several asserts in one test because you have a big graph you want to verify? How 'bout files or maybe razor views? Several asserts often clutter up the tests. Big strings also make the actuall calls hard to see for all that content. Putting big strings in files is a good idea to avoid that, but few people do. It adds another "menial" task when you're in the zone. But what if it was dead easy?

I once maintained a Resharper extension, and their example tests had so called "gold" files that they compared to output. The squigglies was represented by special characters around terms. So they just compared the output of a text renderer to the text in a file. Great idea. One limitation though: with a regular Assert.Equals you just see the segment around the first mismatch. Guess what, there's a tool that's been around for at least 10 years that solves all those issues, and more.

Approval tests, eh?

Sounds a bit like acceptance tests, right? Don't be fooled, it's purpose is to serve all the way down to the "unit test layer" of your tests. I've found it to be a huge timesaver, as well as making my tests so much more clear.

I know you're thinking "Shut up and give me an example, then!", so let's have a look. I've got this unit test from my post about testing razor views that I never really asserted anything in. I just output the result to console and assert inconclusive. Here it is for reference:

[TestFixture]

public class When_Displaying_An_Event

{

[Test]

public void It_Is_Rendered_With_A_Name_Date_And_A_Link()

{

var view = new _Views_Partials_Event_cshtml();

var actionResult = GetConcertEvent();

Assert.AreEqual("Event", actionResult.ViewName);

var renderedResult = view.Render((Event) actionResult.Model);

Console.WriteLine(renderedResult);

Assert.Inconclusive("Way too big to assert here.");

}

}

It outputs the following HTML:

<div>

<a href="https://eventsite/123">

<label>

Concert of your life

</label>

<span>

fredag 31. desember 2049 23.59

</span>

</a>

</div>

Let's see it

Now let's assert this with ApprovalTests. To use it, you just install-package ApprovalTests with your trusty package manager console. Make sure to install it in your test project. ;)

Now instead of Assert, we ask ApprovalTests to Verify our data instead. It even has a special overload for this concrete case: Approvals.VerifyHtml. So we rewrite the test as such:

[Test]

public void It_Is_Rendered_With_A_Name_Date_And_A_Link()

{

var view = new _Views_Partials_Event_cshtml();

var actionResult = GetConcertEvent();

Assert.AreEqual("Event", actionResult.ViewName);

var renderedResult = view.Render((Event) actionResult.Model);

Approvals.VerifyHtml(renderedResult);

}

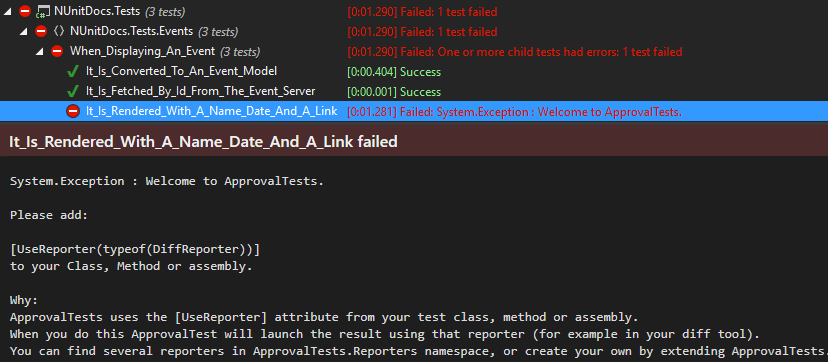

Now when we run our test, we get this nice little welcoming message from ApprovalTests:

It tells us we're missing a vital part: A reporter. It's possible to use DiffReporter to launch your favorite configured difftool. But if you're in Visual Studio, there's a special treat: VisualStudioReporter. Let's add that to our fixture and see what happens:

[UseReporter(typeof(VisualStudioReporter))]

[TestFixture]

public class When_Displaying_An_Event

{

[Test]

public void It_Is_Rendered_With_A_Name_Date_And_A_Link()

{

// ...

}

}

And we run it:

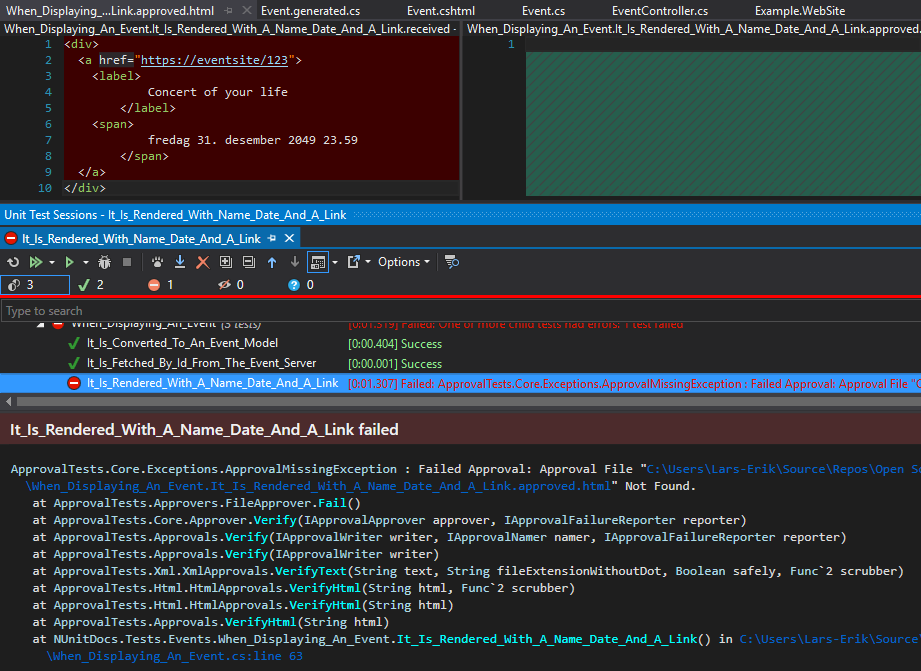

What hits you is probably the big failure statement there, but look again - up at the top there.

We've got a diff opened, the result on the left hand and a big green field on the right side.

What just happened is that ApprovalTests took our result, stored it in a received file, and at the same time wrote an empty "approved" file. It then proceeded to compare, and finally pop a diff of those two files.

Isn't that just beautiful? Everything that makes your test fail in one clear diagram.

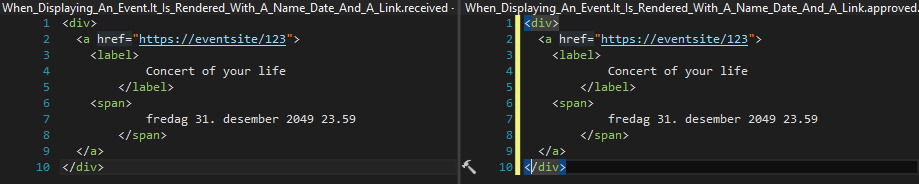

The "procedure to follow" here, is to "approve" results when you're happy. To do that, you just copy and paste. Let's do that now:

If you've got ReSharper, it's probably gonna try to format everything nicely when you paste. To have it in the original, ugly indentation state, press Ctrl+Z (undo) once after pasting.

Regarding the indentation that's off. It seems to be a bug with HTML in the current version of ApprovalTests, so stupid me for choosing this example. I'll update the post if it gets fixed.

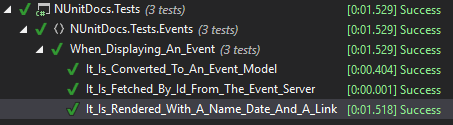

We can now run our test again, and it's gonna pass. When it passes, it doesn't bother to open the diff.

This means we're just gonna get diffs for whatever is currently failing. Even if we run our entire suite of tests. Now there's a couple of housekeeping things to keep in mind:

Commit approvals only

If you were paying attention, you noticed we got two files adjacent to our test source file. One is named [TestFixtureName].[TestMethodName].received.html and one is named [TestFixtureName].[TestMethodName].approved.html. If you ran a test that passed, you'll actually just have your approved file. You want those approved files in source control!

The received files though, might end up not being cleaned up for one or the other reason. Hopefully just that you didn't bother to commit a fully passing build. I'm sure you didn't do that to the master branch, though. In any case, make sure to ignore your received files. This pattern in .gitignore generally does the trick:

*.received.*

That's just the tip of the iceberg

We've seen the VerifyHtml bit. One of my personal favorites is it's sibling VerifyJson. I keep an extension on object in my tests, called .ToJson(). With it, I can just go:

Approvals.VerifyJson(myBigGraph.ToJson());

The diff is done with prettified JSON, so it's super simple to find the property / area that has changed or doesn't work. Knowing the area of the graph should also make it easier to find the usage that is wrong.

There's a vanilla Verify method too, and it saves plain text files. It's useful in cases where you have nice ToString() implementations. Let's try with a "person":

public class Person

{

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public int Age { get; set; }

public override string ToString()

{

return $"{FirstName} {LastName} ({Age})";

}

}

[Test]

public void Comparing_Objects()

{

var person = new Person

{

FirstName = "Lars-Erik",

LastName = "Aabech",

Age = 19

};

Approvals.Verify(person);

}

It produces the following .received file:

Lars-Erik Aabech (19)

It can be approved like that.

We can also do lists with "big brother" VerifyAll:

[Test]

public void Comparing_Lists()

{

var list = new List<Person>

{

new Person {FirstName = "Lars-Erik", LastName = "Aabech"},

new Person {FirstName = "Dear", LastName = "Reader"}

};

Approvals.VerifyAll(list, "");

}

Which, unsurprisingly outputs:

[0] = Lars-Erik Aabech

[1] = Dear Reader

Now how bout that?

I don't know how quickly you got hooked, but I certainly find it sneaking into more and more of my tests.

It can even do images, but I'll let James blog about that one.

So what are you lingering around here for? Run over to nuget and get your copy, or lurk around some more at the ApprovalTests project site. There's great examples, even though they might not be in your favorite language.

Happy approving! :)